How Mitochondria In Bone Cells Boost Bone Health

Explore how mitochondria in bone cells are key to boosting bone health and bone mineralization, providing the structural support our bodies need.

What to know

Healthy mitochondria in bone cells are essential for energy production, which supports bone remodeling and overall bone strength.

Mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to weakened bones, raising the risk of conditions like osteopenia and osteoporosis.

The mitochondria play a critical role in calcium regulation, which is vital for maintaining strong, resilient bones.

Lifestyle factors such as a nutrient-rich diet, regular exercise, and other therapies aimed at improving mitochondrial function can protect bone health and prevent fractures.

Regular bone density scans are important for the early detection of bone issues and for preserving bone health as you age.

Our bones do more than just support our bodies ⸺ they are the living tissue that allows us to move freely, exercise, protect vital organs, and store essential minerals.

Mitochondria in bone cells play a role in bone health. They encourage bone remodeling, a vital bone breakdown and formation process that maintains bone strength and optimal function.

This article explores how skeletal cells’ mitochondria generate the energy needed for effective bone remodeling and the importance of maintaining bone health throughout life.

A Word About Bone Disease

Keeping bones strong is critical at any age, especially in older adults at risk for falls, fractures, and bone diseases like osteopenia and osteoporosis. Osteopenia occurs when bone mineral density is low but not low enough to be considered osteoporosis, while osteoporosis is a more advanced loss of bone cells and bone density. Both conditions can affect physical function and increase the risk of fractures; therefore, keeping our mitochondria healthy and full of energy is paramount.

Osteoporosis is often considered a women's disease primarily because of its higher prevalence in women, especially post-menopause. However, research shows that up to 25% of fractures in people over the age of 50 years occur in men.[1] Unfortunately, osteoporosis in men often goes underdiagnosed and can lead to severe health consequences, including fractures and reduced mobility.

While osteoporosis itself is not usually fatal, complications that arise from fractures can be deadly. Fractures often lead to a downward spiral in both physical and mental health, and hip fractures, specifically, are associated with an increased risk of death, especially in the first year after the fracture occurs.[2]

This makes bone health a critical concern for aging men as well as for women.

The Mitochondrial-Bone Connection

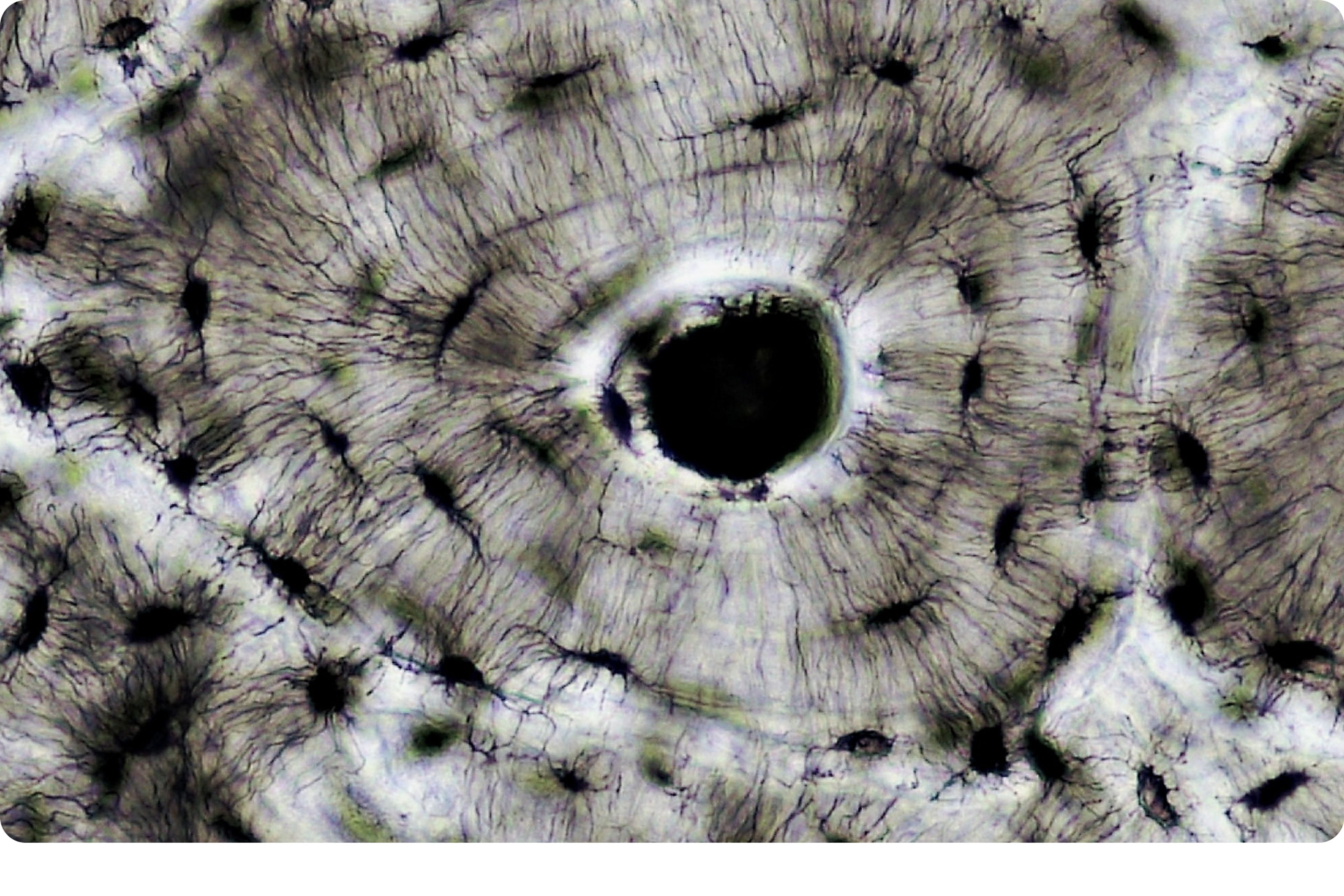

Mitochondria are the mighty cellular structures that generate energy for vital functions, including the energy required to maintain strong bones. Like all cells in the body, our bone cells need energy to thrive. The mitochondria provide crucial energy to osteoblasts and osteoclasts, the bone cells heavily involved in bone remodeling. These two cells play a foundational role in the delicate balance of maintaining bone strength and density.

The remodeling process is non-negotiable for bone health, as it continuously breaks down and rebuilds new bone. According to the research, there are two key ways the mitochondria support bone health.

Serves as an energy supply for bone cells

The mitochondria ensure our bones remain resilient and strong throughout life by providing energy to our bone cells. They do this by ensuring that osteoblasts rebuild new, healthy bone when osteoclasts break down bone as a necessary part of maintaining mineral balance in the body.

While there are several causes of weak and brittle bones, research shows that healthy mitochondria in bone cells can support the bone mineralization process and mineral absorption in the bone. Bone mineralization is how bones become strong and dense—it's when minerals like calcium and phosphorus are absorbed and deposited into the bone tissue. These minerals harden the bones, giving them strength and durability.

Mitochondria help power these processes by providing the energy that bone cells need to efficiently absorb and use these minerals. Mitophagy, the body’s efficient method of removing old, damaged mitochondria and recycling them, is key to creating the efficiently functioning mitochondria needed to supply energy to bone cells.[3]

The bottom line is that the mitochondria can support osteoblast activity so the bone cells can build new, more resilient bone tissue.[4]

Supports calcium regulation

Calcium is needed for functions in the body other than just in bone. In order to maintain blood and cellular calcium levels, the body will often pull calcium from bone for use in other areas throughout the body.

In addition to generating cellular energy, the mitochondria play a central role in maintaining intracellular calcium balance. While the connection between mitochondrial and bone calcium homeostasis is not fully understood, emerging research suggests that there is a link between these two processes.[5]

The Impact of Mitochondrial Dysfunction on Bones

Mitochondrial dysfunction, a hallmark of aging, can promote the pathways leading to bone density loss via a few distinct pathways. When these pathways are negatively impacted, there is an increased risk of bone weakness, bone fracture, and conditions like osteoporosis.

Impaired bone regeneration

When the mitochondria are not functioning optimally, bone cells may lack the energy to form new bone, leading to slower bone regeneration and potentially weaker bones. In particular, this dysfunction can reduce the energy provided to the osteoblasts, the bone cells responsible for forming new bone. This decrease in bone formation can lead to weaker bones and an impaired ability to repair bone damage.[6]

Increased bone resorption

Mitochondrial dysfunction impairs the regeneration of new bone by increasing osteoclast activity, the cells that break down bone. An increase in this activity can reduce the amount of new, healthy bone formed as the osteoblasts struggle to keep up with the activity of the bone-dissolving osteoclasts.[7]

This imbalance of bone remodeling activity can lead to bone loss over time and, eventually, to conditions like osteopenia and osteoporosis that weaken the bones.

Oxidative stress

Poor mitochondrial health can also contribute to increased oxidative stress, which is linked to bone density loss and an increased risk of fractures. Oxidative stress is an imbalance of compounds called free radicals that can cause damage to bone cells and even contribute to disease.[8]

Keeping your mitochondria healthy may help to protect the body from bone weakness due to oxidative stress.

What Can You Do to Improve Bone Health

While mitochondria and bone health are intricately linked, the health of your mitochondria and your bones is not pre-determined. You can support your bone health through various lifestyle factors, starting with healthy eating and exercise habits and preventative testing.

Diet

Certain nutrients can help build and maintain strong bones.

Calcium - Calcium helps to harden and strengthen bone, making it less likely to weaken or break after a fall.[9]

The best calcium sources are dairy or calcium-fortified non-dairy products, tofu, sardines, and leafy greens like spinach, kale, and bok choy.

Vitamin D - Another essential bone-supporting nutrient is vitamin D, as it helps bones absorb calcium. [11]Research shows adequate vitamin D can help prevent fractures and improve bone mineral density, helping to maintain strong bones that are less susceptible to breakage.[10]

Salmon, tuna, mushrooms, and fortified dairy and non-dairy products are the best food sources for vitamin D. We also naturally make vitamin D in our skin from the sun; however, most of us don’t spend enough time outdoors, especially in winter months, to make enough. For many, a vitamin D supplement may be the best option for ensuring you get adequate levels of this nutrient.

Magnesium - Magnesium is another essential mineral for happy bones, and research shows eating adequate magnesium is associated with increased bone mineral density[12]. Magnesium is found in both plant and animal foods such as nuts, seeds, beans, spinach, and salmon.

Vitamin K - Vitamin K plays a strong role in bone health by supporting Vitamin D and also promoting bone density and remodeling. While we get the majority of active vitamin K from foods like dark green leafy vegetables like spinach and collard greens, vitamin K is also a postbiotic made by our gut microbiome.

Phosphorus - The mineral phosphorus is the second most abundant mineral in bones, after calcium, so sufficient intake is a must for bone health. Dairy, legumes, fish, and seafood are great sources of dietary phosphorus.

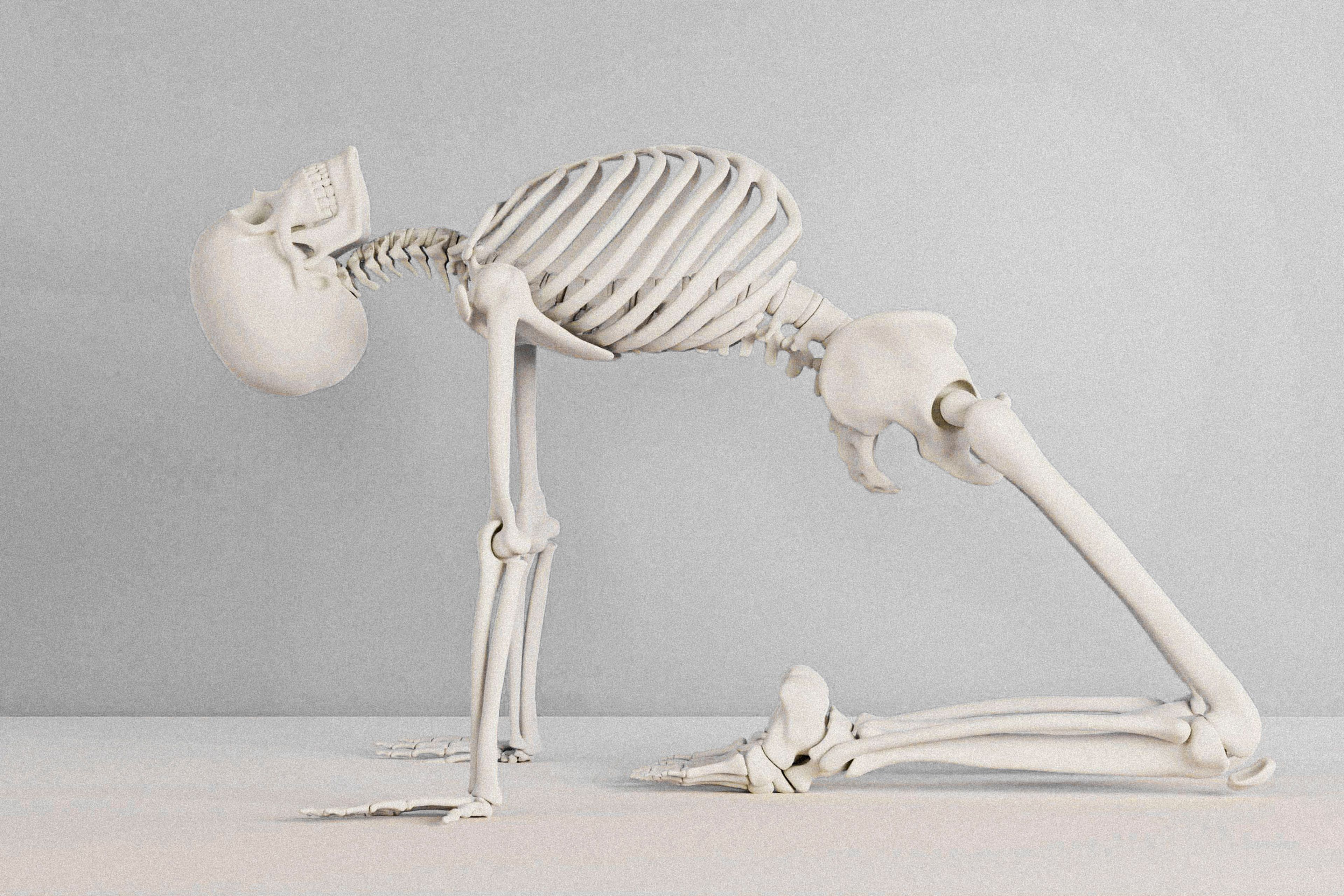

Exercise

Physical activity is also important to support strong bones. A combination of both strength and cardio exercises is best, as they both work together to build strong bones.

Weight-bearing cardio activities like brisk walking, jogging, and racket sports are great options to force bones to work harder. For strength, exercises like weight machines, free weights, resistance bands, and bodyweight exercises make the muscles work harder and, therefore, stronger.

Get a bone density scan

Bone density and longevity are tightly linked, and getting a bone density scan is a great way to know if your bones are healthy. A bone density scan uses X-rays to measure bone mineralization markers such as bone mineral content, thickness, and overall strength. This test is often used as a screening measure to detect bone issues early on and is a common diagnostic tool for osteopenia and osteoporosis.

The CDC recommends osteoporosis screening for women 65 years old or older and for women who are 50 to 64 and have certain risk factors, such as having a parent who has broken a hip. [13]The recommendation for men is for those over the age of 70.[14]

Many physicians are now proactively recommending DEXA scans at an earlier age, as these low-risk procedures can help identify low bone density before significant bone loss occurs. Detecting low bone density in patients in their 50s and 60s allows for timely intervention when treatments are more likely to be effective, potentially preventing the progression to osteopenia or osteoporosis later in life.

Ask your doctor about this test if you’re concerned about your bone density and strength.

Final Words

Improving the health of the mitochondria in bone cells can help maintain strong, resilient bones by supporting bone remodeling. By ensuring that your mitochondria function optimally, you can help maintain bone density and reduce the risk of fractures that come with aging.

Lifestyle approaches such as targeted nutrition and exercise hold great promise in bolstering bone strength. Getting regular bone density screenings can also help you to be proactive against conditions like osteopenia and osteoporosis.

All of these strategies work to preserve bone health, optimizing mobility so you can move freely and live an active life without restrictions.

Authors

Written by

Dietitian-Nutritionist, and Health Content Writer

Reviewed by

Director Science Communications

References

- ↑

Björnsdottir S, Clarke BL, Mannstadt M, Langdahl BL. Male osteoporosis-what are the causes, diagnostic challenges, and management. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2022 Sep;36(3):101766. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2022.101766. Epub 2022 Aug 9. PMID: 35961836.

- ↑

Office of the Surgeon General (US). Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2004. 5, The Burden of Bone Disease. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK45502/ (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK45502/&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1729205623605970&usg=AOvVaw2OBmNG5Q2KdhP8Fq43-6ah)

- ↑

Joonho Suh, Yun-Sil Lee, The multifaceted roles of mitochondria in osteoblasts: from energy production to mitochondrial-derived vesicle secretion, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, Volume 39, Issue 9, September 2024, Pages 1205–1214, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbmr/zjae08

- ↑

Joonho Suh, Yun-Sil Lee, The multifaceted roles of mitochondria in osteoblasts: from energy production to mitochondrial-derived vesicle secretion, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, Volume 39, Issue 9, September 2024, Pages 1205–1214, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbmr/zjae08

- ↑

Kawahara I, Koide M, Tadokoro O, Udagawa N, Nakamura H, Takahashi N, Ozawa H. The relationship between calcium accumulation in osteoclast mitochondrial granules and bone resorption. Bone. 2009 Nov;45(5):980-6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.07.010. Epub 2009 Jul 21. PMID: 19631304.

- ↑

Joonho Suh, Yun-Sil Lee, The multifaceted roles of mitochondria in osteoblasts: from energy production to mitochondrial-derived vesicle secretion, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, Volume 39, Issue 9, September 2024, Pages 1205–1214, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbmr/zjae08

- ↑

Dobson, P.F., Dennis, E.P., Hipps, D. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction impairs osteogenesis, increases osteoclast activity, and accelerates age related bone loss. Sci Rep 10, 11643 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68566-2

- ↑

Yang S, Feskanich D, Willett WC, Eliassen AH, Wu T. Association between global biomarkers of oxidative stress and hip fracture in postmenopausal women: a prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(12):2577-2583. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2302

- ↑

Vannucci L, Fossi C, Quattrini S, et al. Calcium Intake in Bone Health: A Focus on Calcium-Rich Mineral Waters. Nutrients. 2018;10(12):1930. Published 2018 Dec 5. doi:10.3390/nu10121930

- ↑

Burt LA, Billington EO, Rose MS, Raymond DA, Hanley DA, Boyd SK. Effect of High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation on Volumetric Bone Density and Bone Strength: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;322(8):736–745. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.11889

- ↑

Rodríguez-Olleros Rodríguez C, Díaz Curiel M. Vitamin K and Bone Health: A Review on the Effects of Vitamin K Deficiency and Supplementation and the Effect of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants on Different Bone Parameters. J Osteoporos. 2019 Dec 31;2019:2069176. doi: 10.1155/2019/2069176. PMID: 31976057; PMCID: PMC6955144.

- ↑

Rondanelli M, Faliva MA, Tartara A, et al. An update on magnesium and bone health. Biometals. 2021;34(4):715-736. doi:10.1007/s10534-021-00305-0

- ↑

"Facts About Bone Density (DEXA Scan)." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 20 Feb. 2024, www.cdc.gov/radiation-health/data-research/facts-stats/dexa-scan.html (https://www.google.com/url?q=http://www.cdc.gov/radiation-health/data-research/facts-stats/dexa-scan.html&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1729205623607256&usg=AOvVaw2T-4kiIMyq0l1kZ8LaMkB3). Accessed 13 Oct. 2024.

- ↑

Bello MO, Rodrigues Silva Sombra L, Anastasopoulou C, et al. Osteoporosis in Males. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538531/ (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538531/&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1729205623607990&usg=AOvVaw0TVv75dNnNC1FwKKYdB4OR)