Andropause: Your Guide to Testosterone Decline and Aging

Andropause, or “male menopause,” is the age-related decline in testosterone. Learn the longevity effects of this change in sex hormone levels.

What to know

Andropause is the term for age-related testosterone decline.

Testosterone levels in men typically decline around age 35.

Andropause can lead to symptoms such as low energy and sexual dysfunction. It may also contribute to age-related muscle loss, chronic disease, and increased risk of early mortality.

Age-related testosterone decline also impacts mitochondrial health, as sex hormones help keep these organelles functioning well.

Certain lifestyle interventions, like exercise and a healthy diet, may help slow testosterone decline.

Medical Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to replace the guidance from a medical professional.

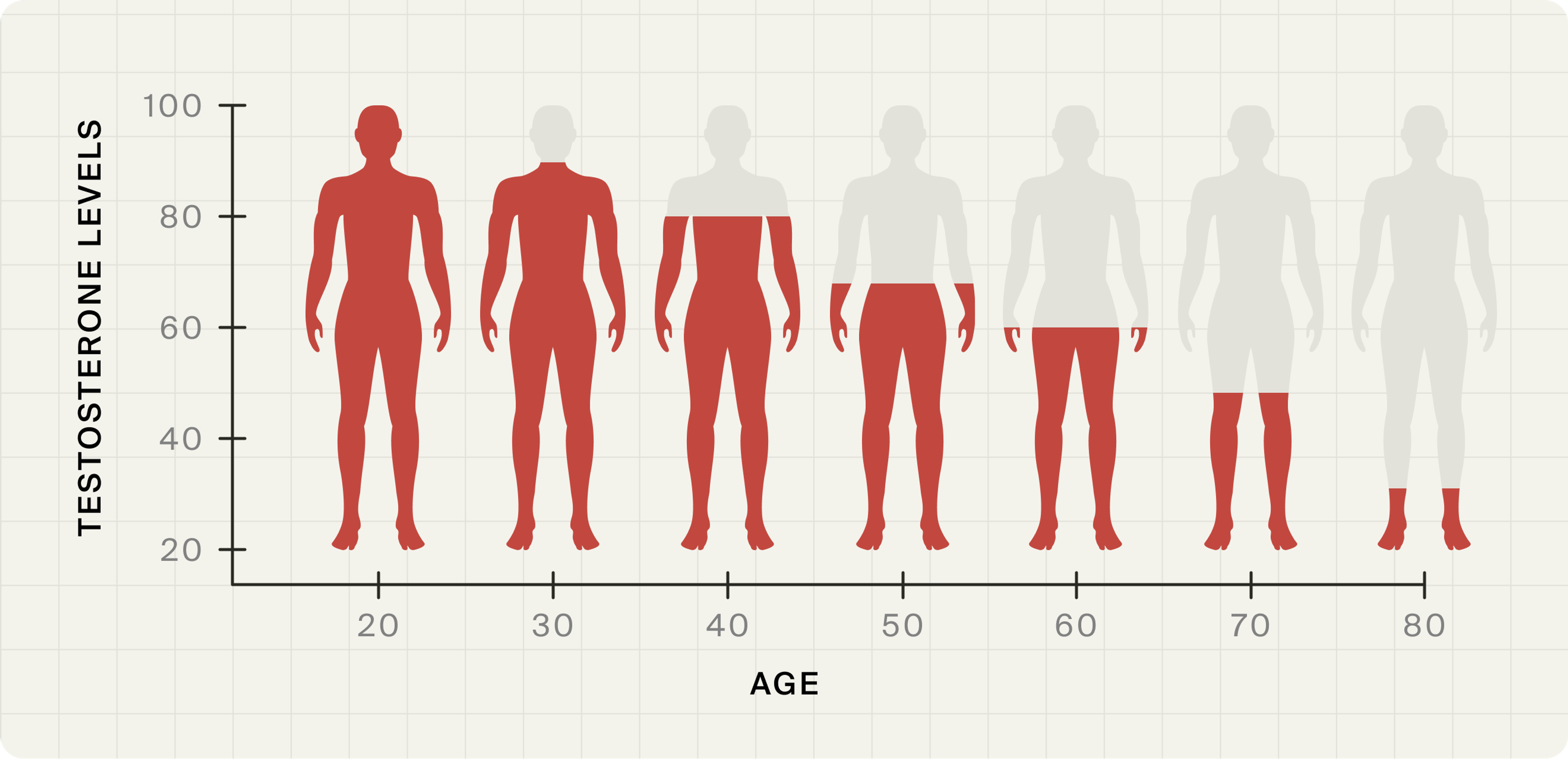

By the time a man turns 75, his circulating testosterone levels will be about 30 percent lower than they were when he was 25. This type of age-related hormone change has sometimes been called “male menopause.”[1]

But that description’s not quite right. When women undergo menopause, their hormones shift drastically over a few years of time, and it’s marked by a full year of cessation of their menstrual cycle. Men, of course, don’t menstruate. More importantly, “male menopause,” also called “andropause,” is a much slower, more gradual decline in hormones.

Studies suggest that starting around age 35, men’s testosterone levels fall by close to 1 percent per year. Andropause symptoms include fatigue, irritability, and sexual dysfunction, but also more serious health consequences. It’s associated with metabolic syndrome, diabetes, mental health struggles, and even early death.[2]

Read on to learn more about the causes and symptoms of andropause, and what you can do to slow this age-related decline.

What is Andropause?

The term andropause (also sometimes referred to as “viropause”) has gained popularity in the media, but it is not a formally recognized clinical diagnosis. In scientific literature, the condition is more accurately referred to as “late-onset hypogonadism,” a complex syndrome involving biochemical, physical, and psychosocial changes in aging men.[3]

Testosterone decline in men can occur at a relatively young age, roughly around 35 years. Why does this happen? In men, testosterone production is controlled by a hormone loop that starts in the brain. The hypothalamus, a region deep in the brain, sends out pulses of a hormone called gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). This signals the pituitary gland, located just beneath the brain, to release another hormone called luteinizing hormone (LH). LH then travels through the bloodstream to the testes, where it stimulates Leydig cells to produce testosterone.[4]

As men age, this system doesn’t work as efficiently. The pulses of GnRH become weaker or less regular, the pituitary becomes less responsive, and the Leydig cells don’t respond as well to LH. These combined changes lead to a gradual drop in testosterone levels over time.[5]

Testosterone decline in men

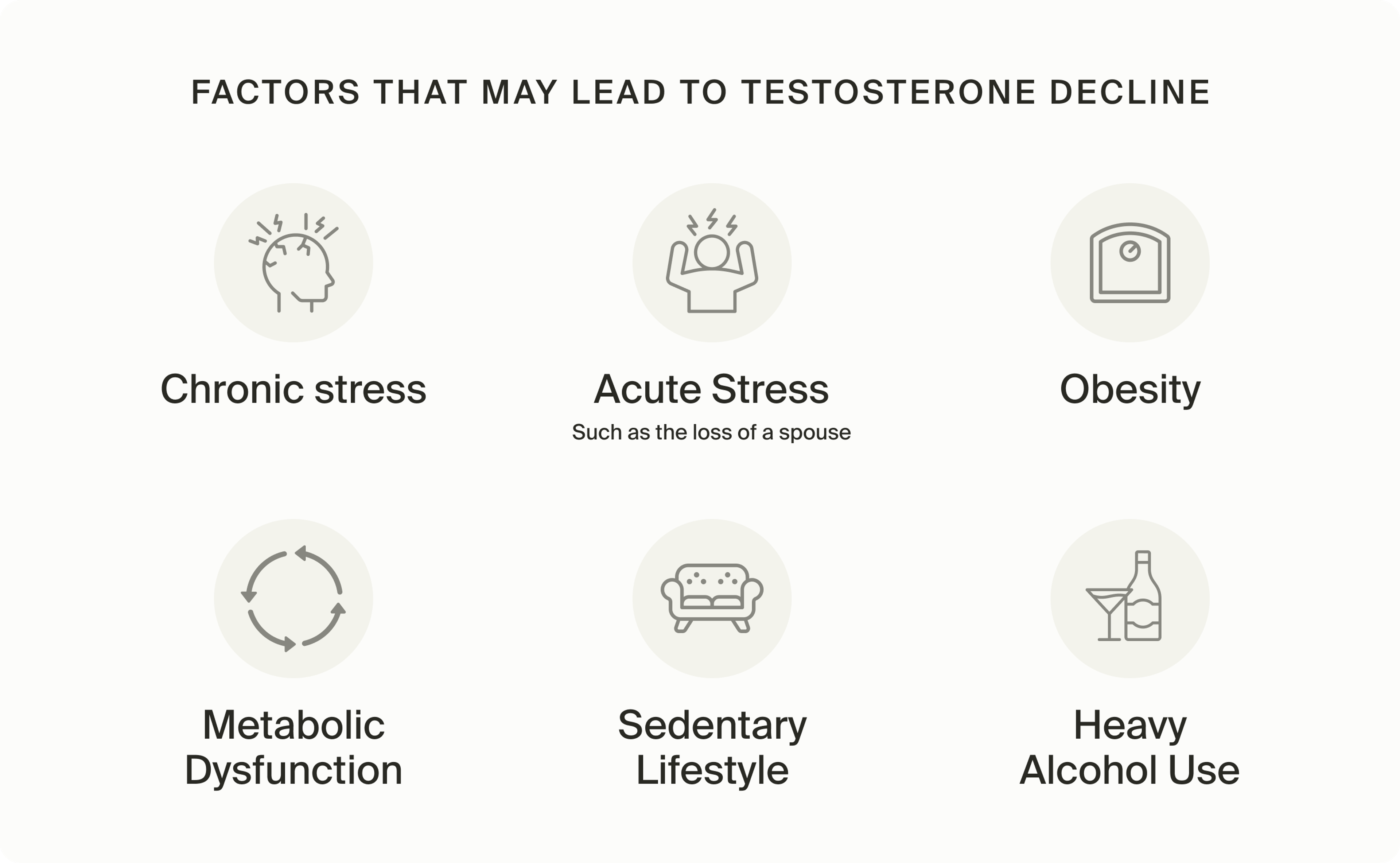

A drop in testosterone levels as we get older is normal, but these age-related hormone changes can occur at varying ages and rates for different men. Research suggests that both genetics, lifestyle, and health will play a role in hormonal decline.

Symptoms of Andropause

Since testosterone is a sex hormone, it’s no surprise that when it declines, you could experience sexually-related symptoms: Late-stage hypogonadism is associated with decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, infertility, and a reduction in early morning erections.[6]

But our bodies use testosterone for much more than reproduction, so andropause touches basically every part of our lives. Age-related hormone changes can impact everything from energy levels to mood to body composition. It also impacts factors that can have serious consequences for our health span.

Andropause is associated with:

• Lower muscle mass: Our bodies use testosterone to build and maintain muscle. Age-related reductions in testosterone levels are one contributor to age-related muscle loss, or sarcopenia. Less muscle means more frailty, which reduces healthy longevity.[7]

• Increased BMI and waist circumference: Lower testosterone in men is linked with bigger bodies, and more importantly, larger waists. Men with the largest waist sizes tend to have the lowest levels of testosterone.[8] And bigger waists put men at a higher risk of heart attack.[9]

• Reduced bone density, which can lead to osteoporosis, a condition that is underdiagnosed and therefore usually undermanaged in men.[10]

• Increases in markers for cardiovascular disease, including elevated serum triglycerides.[11]

• Increased risk of diabetes: Decreased testosterone levels are associated with poor glycemic control and increased insulin resistance,[12] increasing the risk for type 2 diabetes.[13]

• Impacts on brain health: Older males with decreased testosterone levels may experience cognitive decline, and low testosterone levels are associated with Alzheimer’s.[14]

Andropause and Mitochondrial Function

While mitochondria are known for making cellular energy—they’re the “powerhouses of the cell,” after all—the organelles are also involved in the testosterone-making process. After Leydig cells interact with luteinizing hormone to start the testosterone-making cascade, the testosterone-making process depends on the mitochondria in those cells being able to transport cholesterol molecules into the inner membrane of each mitochondria.[15]

When mitochondria in Leydig cells aren’t working right, because they’re dysfunctional or aren’t undergoing mitophagy to kill off old, malfunctioning mitochondria, your Leydig cells don’t make as much testosterone.[16]

This creates a compounding effect because sex hormones, like testosterone, are important for keeping mitochondria functioning well. So age-related loss of testosterone makes mitochondria function worse … and worse-functioning mitochondria aren’t as good at making testosterone, reducing levels.[17]

Andropause and Longevity

With its association with cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, and diabetes, it’s no surprise that a 2016 research review of large studies found a correlation between low testosterone levels and a greater risk of mortality.[18]

But it’s also associated with reduced healthspan. Low testosterone has been linked to frailty, low energy and fatigue, joint pain, cognitive impairment, and several other symptoms that impact health status and overall quality of life.[19]

Lifestyle Interventions That Can Boost Testosterone

Prescriptions for testosterone replacement therapy, or TRT, have exploded in recent years: Between 2016 and 2019, the number of doctors who prescribed testosterone grew by 28 percent,[20] and a 27% increase in the number of people being treated with TRT between 2016 and 2022.[21]

But if you’re experiencing andropause symptoms, or your doctor has measured your T and it’s low, he or she might not dive right into prescribing TRT. They may first try to have you do some of these lifestyle interventions that have been shown to improve T levels (and just happen to improve health in general):

For older men who are not currently active, exercise can help increase T levels: A study of lifelong sedentary men (~62 years old) found that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) led to a 17% increase in total testosterone and a 4.5% increase in free testosterone after a combination of conditioning and HIIT training.[22]

Weight lifting may have an even greater effect. A study that compared 16 weeks of resistance to aerobic training in men aged 70–80 and found that testosterone levels were higher in the resistance-trained men. Notably, though, after 4 weeks of detraining, this increase in testosterone was lost.[23]

Being overweight is associated with lower testosterone levels. One study found that when BMI increases by 4-5 points, testosterone levels fall the same amount as they would over 10 years of aging.[24] Losing weight while testosterone levels are lower can be challenging, but if you can, it might help improve your levels. In one study of 900 middle-aged men, losing around 17 pounds lowered the prevalence of low testosterone by 46%.[25]

In a Japanese study, a so-called “low T-related dietary pattern” made up of lots of bread and pastries, desserts, and dining out was associated with lower testosterone levels than eating more dark green vegetables and more meals at home.[26]

Conclusions and What to Do

Age-related testosterone decline is normal, but the speed of this decline depends on several factors. Some are in your control, like lifestyle, and others, like your genetics, aren’t. If you’re experiencing the symptoms of andropause—low energy, sexual dysfunction, or changes in mood—talk to your doctor about having your testosterone levels tested, and about lifestyle changes you can make to try to address it.

Authors

Written by

Health & Fitness Writer

Reviewed by

Director Science Communications

References

- ↑

Decaroli MC, Rochira V. Aging and sex hormones in males. Virulence. 2017;8(5):545-570. doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1259053

- ↑

"Male Menopause: Myth or Reality?" Mayo Clinic, 26 Mar. 2025, www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/mens-health/in-depth/male-menopause/art-20048056 (https://www.google.com/url?q=http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/mens-health/in-depth/male-menopause/art-20048056&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571663833&usg=AOvVaw0tDvkaLgqpPCszLxqg7u0u). Accessed 4 Jun. 2025.

- ↑

Gryzinski, G.M., Bernie, H.L. Testosterone deficiency and the aging male. Int J Impot Res 34, 630–634 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00555-7 (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00555-7&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571664731&usg=AOvVaw3zpYVDaxI0Xi_ISnIVeEyW)

- ↑

Cheng H, Zhang X, Li Y, Cao D, Luo C, Zhang Q, Zhang S, Jiao Y. Age-related testosterone decline: mechanisms and intervention strategies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2024 Nov 14;22(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s12958-024-01316-5. PMID: 39543598; PMCID: PMC11562514.

- ↑

Cheng H, Zhang X, Li Y, Cao D, Luo C, Zhang Q, Zhang S, Jiao Y. Age-related testosterone decline: mechanisms and intervention strategies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2024 Nov 14;22(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s12958-024-01316-5. PMID: 39543598; PMCID: PMC11562514.

- ↑

Sizar O, Leslie SW, Schwartz J. Male Hypogonadism. [Updated 2024 Feb 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532933/ (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532933/&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571671485&usg=AOvVaw3k1UcXz9TOwTkcWA8tPGR8)

- ↑

Shin MJ, Jeon YK, Kim IJ. Testosterone and Sarcopenia. World J Mens Health. 2018;36(3):192-198. doi:10.5534/wjmh.180001

- ↑

Svartberg J, von Mühlen D, Sundsfjord J, Jorde R. Waist circumference and testosterone levels in community dwelling men. The Tromsø study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19(7):657-663. doi:10.1023/b:ejep.0000036809.30558.8f

- ↑

Peters SAE, Bots SH, Woodward M. Sex Differences in the Association Between Measures of General and Central Adiposity and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction: Results From the UK Biobank. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(5):e008507. Published 2018 Feb 28. doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.008507

- ↑

Rochira V. Late-onset Hypogonadism: Bone health. Andrology. 2020 Nov;8(6):1539-1550. doi: 10.1111/andr.12827. Epub 2020 Jun 17. PMID: 32469467.

- ↑

anji F, Nanbu H, Nishimoto D, Kawajiri M. Psychosocial Factors and Andropause Symptoms Among Japanese Men: An Internet-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Mens Health. 2025;19(1):15579883241312836. doi:10.1177/15579883241312836

- ↑

Khalil, S.H.A., Dandona, P., Osman, N.A. et al. Diabetes surpasses obesity as a risk factor for low serum testosterone level. Diabetol Metab Syndr 16, 143 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-024-01373-1 (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-024-01373-1&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571673427&usg=AOvVaw01R3u4hj0qXoXsamnftbWU)

- ↑

Yao QM, Wang B, An XF, Zhang JA, Ding L. Testosterone level and risk of type 2 diabetes in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocr Connect. 2018 Jan;7(1):220-231. doi: 10.1530/EC-17-0253. Epub 2017 Dec 12. PMID: 29233816; PMCID: PMC5793809.

- ↑

Yeap, B.B., Flicker, L. Testosterone, cognitive decline and dementia in ageing men. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 23, 1243–1257 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-022-09728-7 (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-022-09728-7&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571675774&usg=AOvVaw3-ixRs-eQglNoCs53UvYUW)

- ↑

Cheng, H., Zhang, X., Li, Y. et al. Age-related testosterone decline: mechanisms and intervention strategies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 22, 144 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-024-01316-5 (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-024-01316-5&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571676743&usg=AOvVaw3orqeCYhkM9pk-tvk6JR-z)

- ↑

Cheng, H., Zhang, X., Li, Y. et al. Age-related testosterone decline: mechanisms and intervention strategies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 22, 144 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-024-01316-5 (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-024-01316-5&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571677673&usg=AOvVaw1bzyqqNj8kNm_-sJUzL52K)

- ↑

Velarde, M.C. Mitochondrial and sex steroid hormone crosstalk during aging. Longev Healthspan 3, 2 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-2395-3-2 (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-2395-3-2&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571678383&usg=AOvVaw0bm0lb_3BNRtMLsI8selFs)

- ↑

Decaroli MC, Rochira V. Aging and sex hormones in males. Virulence. 2017;8(5):545-570. doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1259053

- ↑

Testosterone and the aging male: To treat or not to treat?

Bain, Jerald

Maturitas, Volume 66, Issue 1, 16 - 22 - ↑

Sellke N, Omil-Lima D, Sun HH, et al. Trends in testosterone prescription during the release of society guidelines. Int J Impot Res. 2024;36(4):380-384. doi:10.1038/s41443-023-00709-1

- ↑

Selinger S, Thallapureddy A. Cross-sectional analysis of national testosterone prescribing through prescription drug monitoring programs, 2018-2022. PLoS One. 2024 Aug 28;19(8):e0309160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0309160. PMID: 39196907; PMCID: PMC11355536.

- ↑

Bain, J. (2010). Testosterone and the aging male: to treat or not to treat?. Maturitas, 66 1, 16-22 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.009 (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.009&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571682395&usg=AOvVaw0Sr5PkiUBDbbwwKUWMDfSU).

- ↑

Lovell, D., Cuneo, R., Wallace, J., & Mclellan, C. (2012). The hormonal response of older men to sub-maximum aerobic exercise: The effect of training and detraining. Steroids, 77, 413-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2011.12.022 (https://www.google.com/url?q=https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2011.12.022&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571683644&usg=AOvVaw39t-rqhc52iAT1Ac26XTvX).

- ↑

Travison, T. G., Araujo, A. B., Kupelian, V., O’Donnell, A. B., & McKinlay, J. B. (2007). The Relative Contributions of Aging, Health, and Lifestyle Factors to Serum Testosterone Decline in Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 92(2), 549–555. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1859

- ↑

Endocrine Society. "Overweight men can boost low testosterone levels by losing weight." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 25 June 2012. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/06/120625124914.htm (https://www.google.com/url?q=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/06/120625124914.htm&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1749477571686840&usg=AOvVaw2HG2WNO_dn7Rp8edeXv-9W)>

- ↑

Hu TY, Chen YC, Lin P, Shih CK, Bai CH, Yuan KC, Lee SY, Chang JS. Testosterone-Associated Dietary Pattern Predicts Low Testosterone Levels and Hypogonadism. Nutrients. 2018 Nov 16;10(11):1786. doi: 10.3390/nu10111786. PMID: 30453566; PMCID: PMC6266690.

Disclaimer

The information in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. Always consult with your medical doctor for personalized medical advice.